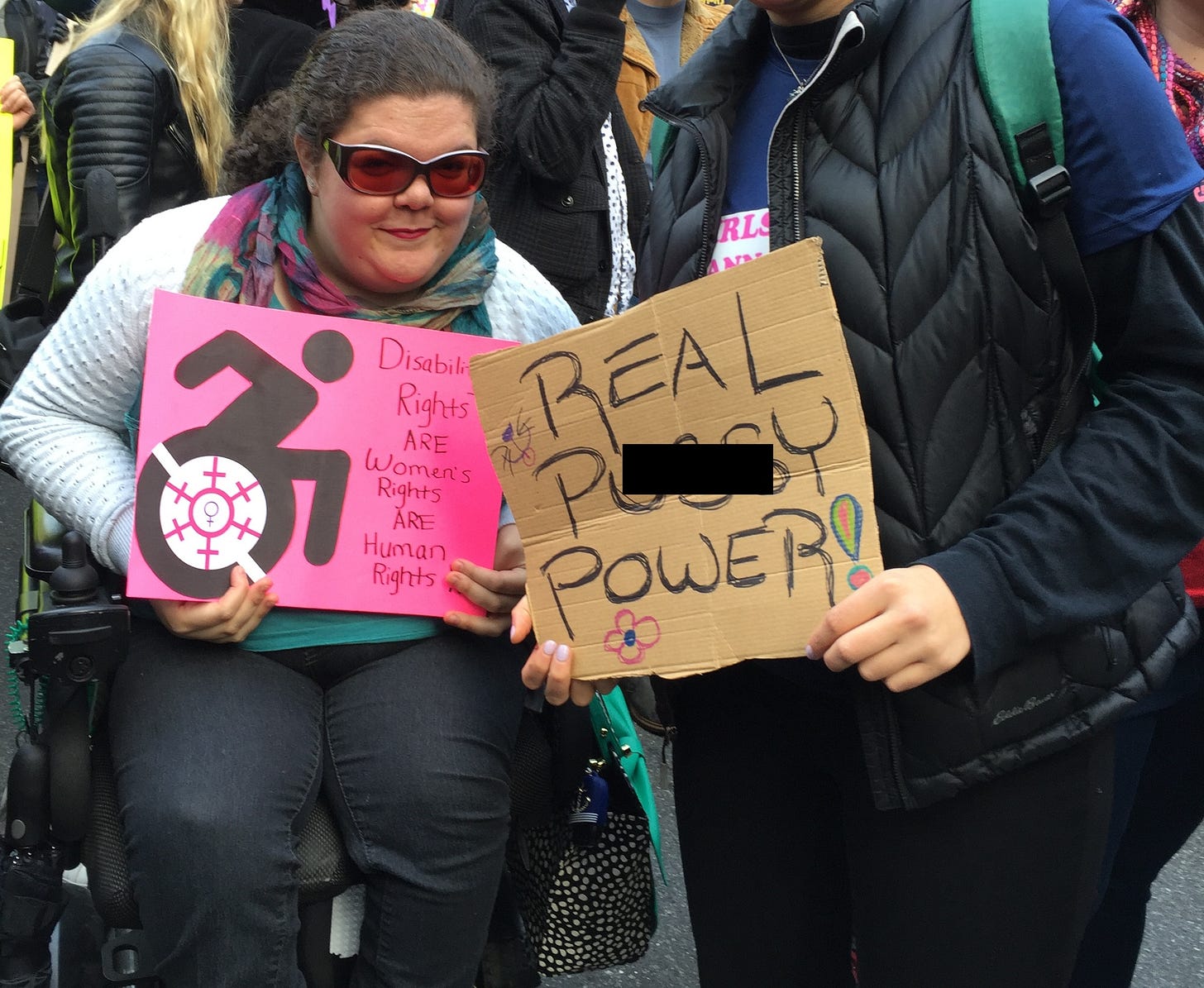

I've Marched, Rallied, and Protested In My Wheelchair. But It's Rarely Accessible.

Who is the revolution for if it's not for everyone?

If the piece below resonates with you, I hope you’ll become part of the Words I Wheel By community!

In 1977, disabled people orchestrated the longest occupation in history of a federal building (the 504 Sit-In) to demand the implementation of regulations protecting against disability discrimination by federally funded programs and activities. In 1978, a group known as "The Gang of 19" put themselves in front of buses for 24 hours to protest inaccessible public transit. In 1990, disability activists marched from the White House to the U.S. Capitol and then hauled themselves up the Capitol steps to demand the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

I am forever indebted to these activists who put their bodies on the line before I even existed, fighting so disabled people could live better lives. I feel an urgent sense of responsibility to honor the legacies of those who came before me by keeping up the fight. And there are indeed many disability activists who have taken up the mantle of physical protest in the years since.

I often think about how powerful it would be for another action like the Capitol Crawl to come together. The optics, the spectacle…it could really have an impact. And I want to be a part of it.

But I am so fearful of what the outcome would be if disabled people engaged in such protests today. Refusing to leave a building. Refusing to move out of the way of a bus. Refusing to get off the steps of the Capitol until getting all the way to the top. I don't think it's an exaggeration to say such acts of defiance in our current society could escalate to a real danger to disabled protestors who are physically unable to quickly escape. And then the justification for the harm would be the false claim that disabled people were the threat, when in fact it's our lives that are actually under threat.

All this is to say, the stakes of protesting have become increasingly, frighteningly high. Of course, plenty of people say that's exactly the point. They say it's a privilege to be able to opt out. They say that if you don't show up, you don't care.

Flipping the Script on Physical Protest

My power wheelchair only goes up to 6 miles per hour and is 2 feet wide. I can't see what's happening in a sea of people who are standing. And people standing up can't see me below the crowd. I can't run away or slip in between anyone. I'm a big, slow moving target. And it honestly feels like I'd be as much of a liability to myself as to others around me. So, while massive crowds aren't safe for anyone, they're an absolute nightmare for me.

It's a privilege to be physically able to flee dangerous situations. And there are many other ways to put up a fight and show you care. Which I do. Deeply.

I have been to marches, rallies, and protests. I have taken to the streets to demonstrate what I believe in. I have the utmost respect for people who continue to do this, especially disabled people. But my disabled and chronically ill body is just not up to the task these days. This has led to a feeling of guilt that was especially strong as the No Kings protests unfolded.

Here's the reality, though. I can barely function in uncontrolled crowds. My power wheelchair is essentially a 400+ lb. tank attached to my butt that makes me lower to the ground than an average height person. No matter how aware I am of surroundings, people who don't use mobility aids don't have the same understanding of the space I occupy.

Imagine these scenarios. They're inconsequential compared to protesting, but they illustrate my main point.

In high school, I was in the ensemble of Bye Bye Birdie. There's a scene where the overwhelming sexual vibes of a hot Elvis-like celebrity make everyone faint. During rehearsals, my fellow cast members tripped and fell all over me so many times while trying to faint. I finally decided it was safer to give up on being part of the chaos and just quietly back off the stage in that moment.

After college, I lived in Washington, DC for an internship. While commuting one evening, the Metro was so delayed that everyone tried to jam into the one that finally arrived. I was nearly knocked out of my wheelchair and someone managed to catch me.

Every time I force my way through Times Square (which I only do because I love theater), oblivious tourists who don't see me end up walking right into me. Last time it happened, as I was rolling along, I ended up trapped in every direction and had to roll over the person's foot just to move forward. She sneered at me as though it was my fault, even though I'd seen her coming and had nowhere to move.

While I lived alone in Manhattan, the armrest on my power wheelchair gave out while I was switching to my manual wheelchair. I lost my balance and I had to let myself slide to the floor to avoid getting hurt. But then I got stuck and my only option was to call an ambulance so the paramedics could pick me up.

I think you get the picture.

Taking Up Space, Breaking Down Systems

To be clear, there is absolutely nothing wrong with taking up space. I’ve had to tell myself this repeatedly, especially since I’ve been called a fire hazard more than once at places that lack accessible seating and force me to sit in the aisle. I resent the implication that I’m in the way of other people exiting in an emergency, rather than also worthy of safety. But sadly, I know there’s some truth behind the notion that my wheelchair can be a danger to others in certain situations.

Anyway, I wrote this in the hopes that if, for the sake of your mind or body's safety, or for the safety of others, you made the decision not to go to the No Kings protest—or, if you've ever worried about not going to a protest in the past, or if you might be uncertain in the future—maybe you'll feel less alone.

Right now, the lethal games this administration is playing are very much intended to push people beyond their capacities toward burnout and breakdown. But let’s remember that there are so many different ways to show up. I truly believe that meaningful and effective efforts toward social justice must allow space for this truth.

We can and must refuse to stay silent, no matter how or from where we communicate. We can and must debunk the barrage of misinformation, push back against the reckless abandon with which supposed lawmakers are breaking laws, call out government-funded eugenics and genocide. We can and must build each other up to tear the systems down.

I know that resources are scarce right now, but if you feel you’ve learned from my work and have the capacity to support, please consider a paid subscription. With a subscription, you can unlock access to my full archive of newsletters since 2021, along with my list of what I recommend watching for authentic disability representation, which I’m committed to keeping updated.

Or, here’s a link for one-time support, which is also greatly appreciated.

And if neither of these are viable for you, not to worry. Either way, I’m truly so glad you’re here. Thank you!

Get Emily. Like I said to the people planning #nokings here I am simply too old for this- and in my day I've been arrested in a pro choice rally in Boston in the 70s, participated in "ring around Honeywell" in the 80s and protect Planned Parenthood in the early 2000s and confronted our Mayor over the lack of affordable housing while I was statistically homeless last year, so I was there in spirit and in truth. I can't even participate fully in our PRIDE parade this weekend but I can and will sit the booth so my cronies can

We do what we can for the causes we believe in.

Well said.

I have a similarly sized wheelchair, and people walk into me on the regular, even though they have an unobstructed view of me. People are oblivious.

I am terrified of getting injured in a setting like the No Kings marches. Particularly after seeing how people are jostled and manhandled whether they are cooperating or not. With the skin fragility I have, it is just not a good gamble for me.

I write, and I donate to organizations I support.

And I fought the good fight inside an extremely ableist educational institution for the majority of my working life.